Online Payment Gateway Service Providers (OPGSP): A Guide

In 2010, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) recognized the surge in e-commerce transactions and decided to establish a framework. They introduced regulations titled "Processing and Settlement of Export Related Receipts Facilitated by Online Payment Gateways."

In essence, these rules allowed specific banks to collaborate with online payment gateway service providers (OPGSPs) to streamline the export-related earnings.

By 2015, the RBI expanded these regulations to include import-related payments as well. They authorized AD Category-I banks to offer similar facilities for imports through agreements with OPGSPs.

This strategic move extended the RBI’s regulatory scope, simplifying international trade transactions for businesses.

Per the OPGSP guidelines, AD Category-I banks serve as intermediaries between the OPGSPs and the RBI, exercising quasi-regulatory control over the operations. However, despite these efforts, challenges persist, hindering smooth cross-border transactions, particularly in emerging business scenarios.

One significant hurdle is the management of risks associated with returns and chargebacks. Many banks remain hesitant to fully embrace the OPGSP framework due to these unresolved challenges.

Consequently, most Indian tech export companies were forced to rely on one of the three options -

- Use a foreign payment gateway like PayPal, Stripe – which involves massive transaction costs

- Set up a subsidiary office in a foreign country or,

- Incorporate in a foreign country and sell globally from there, including India.

The latter seems like an attractive option while also providing additional benefits such as an international presence for the business.

The Present OPGSP Landscape

Currently, the OPGSP facility serves as the primary payment method for more than 300,000 Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises (MSME) exporters throughout India. Despite recent geopolitical tensions in Europe and a global economic recession, India has emerged as a leader in small-value online service exports, aided by the widespread availability of the internet and smartphones even in remote areas.

Introducing OEIF: Potential Reconfiguration

In early 2023, RBI released draft guidelines on the Online Export-Import Facilitators (OEIF), proposing an evolution beyond the OPGSP framework. OEIFs, defined as payment aggregators enabling low-value export and import remittances, might replace the existing system.

While several parts of this draft are quite progressive and well-received by the payments industry, some aspects are not fully clear, and some aspects seem to take a conservative view.

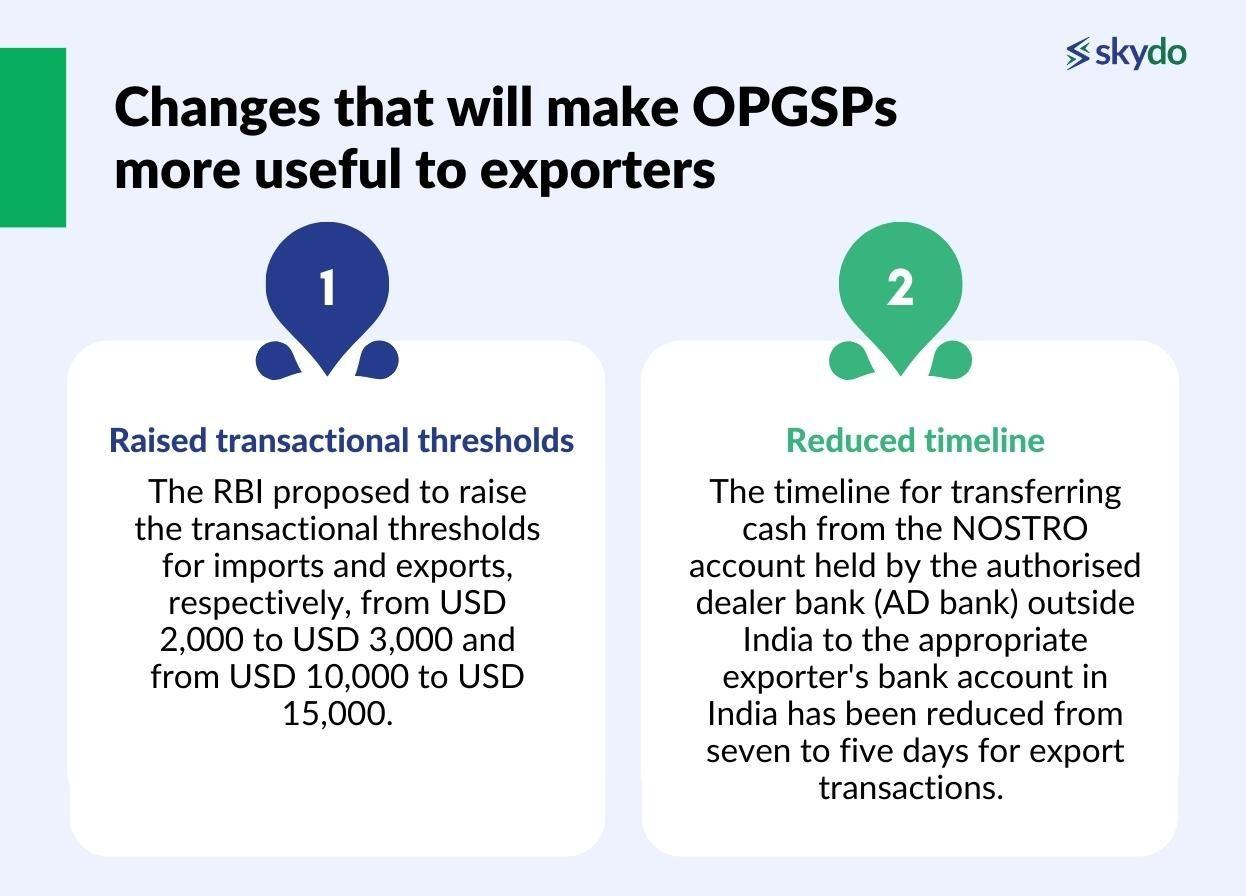

Two major changes that are quite positive and will make OPGSPs more useful to exporters are as follows.

- The RBI proposed to raise the transactional thresholds for imports and exports, respectively, from USD 2,000 to USD 3,000 and from USD 10,000 to USD 15,000.

- The timeline for transferring cash from the NOSTRO account held by the authorised dealer bank (AD bank) outside India to the appropriate exporter's bank account in India has been reduced from seven to five days for export transactions.

However, the RBI aimed to further simplify the OPGSP guidelines for small digital payments linked to import/export transactions through e-commerce and protect the interests of Indian stakeholders.

Yet, some rules under the Draft Guidelines put more burden on the OEIF entities than the previous OPGSP regime. Such as,

- The necessary authorisation under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2007 requires OEIFs that facilitate payments related to imports.

- Mandatory compliance with the baseline technology recommendations is required for OEIFs that facilitate export.

- Compliance with the RBI's KYC requirements is mandatory for overseas importers.

These steps could increase some indirect compliances that apply to PA firms and present practical difficulties for the OEIF entities concerning implementing the guidelines.

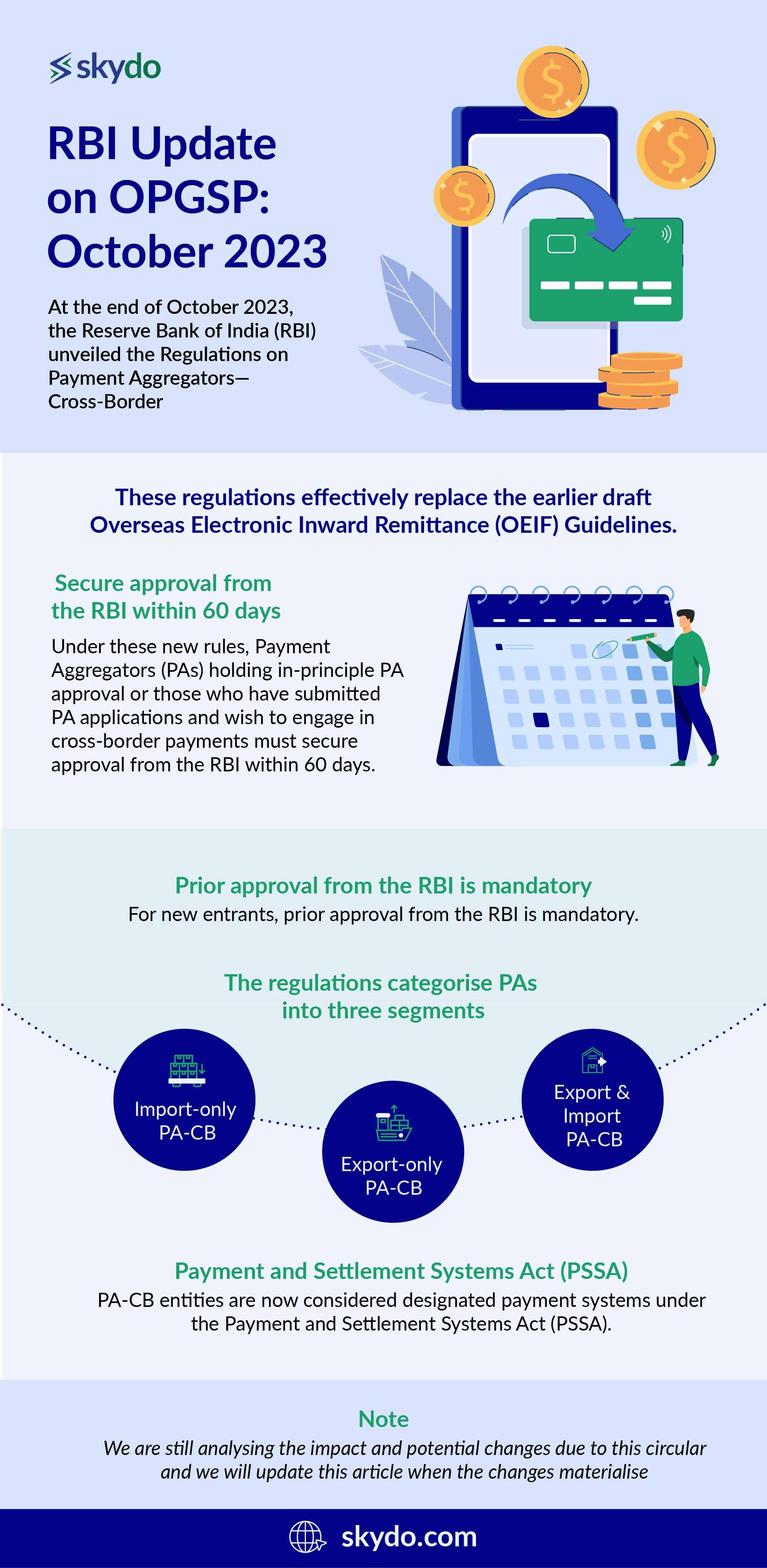

RBI Update on OPGSP: October 2023

At the end of October 2023, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) unveiled the Regulations on Payment Aggregators—Cross-Border, aimed at governing payment aggregators facilitating cross-border transactions for goods and services.

These regulations effectively replace the earlier draft Overseas Electronic Inward Remittance (OEIF) Guidelines.

Under these new rules, Payment Aggregators (PAs) holding in-principle PA approval or those who have submitted PA applications and wish to engage in cross-border payments must secure approval from the RBI within 60 days. For new entrants, prior approval from the RBI is mandatory.

The regulations categorise PAs into three segments:

- import-only PA-CB

- export-only PA-CB

- export and import PA-CB

Each one has specific account maintenance requirements. Additionally, PA-CB entities are now considered designated payment systems under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act (PSSA).

The RBI's recent rule changes, specifically the Regulation on PA-CBs, show that they've listened to feedback from stakeholders. This update resolves difficult requirements and unclear parts in the earlier draft OEIF Circular.

Now, companies involved in import-export deals must get approval from the RBI to act as a PA-CB. This means they have to follow RBI rules, which changes how they do business.

Note: We are still analysing the impact and potential changes due to this circular and we will update this article when the changes materialise

Frequently Asked Questions on OPGSP

Q1. What is an OPGSP?

Ans: An OPGSP stands for Online Payment Gateway Service Provider. It is a type of payment aggregator that facilitates online payment transactions for import and export-related payments, regulated by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) under specific guidelines.

Q2. What is the meaning of OPGSP in RBI?

Ans: In RBI, OPGSP full form is Online Payment Gateway Service Providers, which are payment aggregators that enable the processing and settlement of import and export-related payments, as per the RBI's regulatory framework and guidelines.

Q3. What is the limit of OPGSP?

Ans: The RBI has set transactional thresholds for OPGSPs, with different limits for import and export transactions. The transaction limits were proposed to be raised from USD 2,000 to USD 3,000 for imports and from USD 10,000 to USD 15,000 for exports under the draft guidelines.

Q4. What are the documents required for opening an account in Online Payment Gateway Service Providers (OPGSP)?

Ans: The specific documents required for opening an account with OPGSPs may vary, but typically, they may include identification and business documents, as well as compliance with RBI's KYC requirements and other regulatory guidelines.

Q5. What type of accounts can be opened by OPGSP?

Ans: OPGSPs facilitate accounts for processing online payments, primarily for import and export-related transactions, as governed by the RBI's guidelines.

Q6. How Export Bill Regularisation would happen for end exporters receiving money through OPGSP?

Ans: Export Bill Regularisation for end exporters receiving money through OPGSPs would involve compliance with the RBI's guidelines, ensuring the proper transfer of funds from the NOSTRO account held by the authorized dealer bank (AD bank) outside India to the exporter's bank account in India, with a reduced timeline from seven to five days for export transactions, as per the draft guidelines.